Exploratory Data Analysis#

EDA is the process of performing initial investigations on data to discover patterns, spot anomalies, test hypothesis and check assumptions.

EDA is important for the following reasons, it helps to:

Understand the data better.

Identify the outliers.

Identify the missing values.

Relationship between variables.

Normality of the data.

Outliers.

Correlation between variables.

Distribution of the data. etc.

To start with EDA, we need to understand the problem statement.

Understand the problem. We’ll look at each variable and do a philosophical analysis about their meaning and importance for this problem.

Univariable study. We’ll just focus on the dependent variable (‘SalePrice’) and try to know a little bit more about it.

Multivariate study. We’ll try to understand how the dependent variable and independent variables relate.

Basic cleaning. We’ll clean the dataset and handle the missing data, outliers and categorical variables.

Test assumptions. We’ll check if our data meets the assumptions required by most multivariate techniques.

Now, it’s time to have fun!

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import norm

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

from scipy import stats

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore')

%matplotlib inline

About the dataset

The dataset we’ll use is the well-known Ames Housing dataset. It is a dataset with 81 variables. The goal is to predict the price of a house based on its features.

The dataset is available on Kaggle.

To understand the description of the columns in teh dataset, lets load house_price_data_description.txt file.

# read teh data description file

with open('house_price_data_description.txt', 'r') as file:

print(file.read())

MSSubClass: Identifies the type of dwelling involved in the sale.

20 1-STORY 1946 & NEWER ALL STYLES

30 1-STORY 1945 & OLDER

40 1-STORY W/FINISHED ATTIC ALL AGES

45 1-1/2 STORY - UNFINISHED ALL AGES

50 1-1/2 STORY FINISHED ALL AGES

60 2-STORY 1946 & NEWER

70 2-STORY 1945 & OLDER

75 2-1/2 STORY ALL AGES

80 SPLIT OR MULTI-LEVEL

85 SPLIT FOYER

90 DUPLEX - ALL STYLES AND AGES

120 1-STORY PUD (Planned Unit Development) - 1946 & NEWER

150 1-1/2 STORY PUD - ALL AGES

160 2-STORY PUD - 1946 & NEWER

180 PUD - MULTILEVEL - INCL SPLIT LEV/FOYER

190 2 FAMILY CONVERSION - ALL STYLES AND AGES

MSZoning: Identifies the general zoning classification of the sale.

A Agriculture

C Commercial

FV Floating Village Residential

I Industrial

RH Residential High Density

RL Residential Low Density

RP Residential Low Density Park

RM Residential Medium Density

LotFrontage: Linear feet of street connected to property

LotArea: Lot size in square feet

Street: Type of road access to property

Grvl Gravel

Pave Paved

Alley: Type of alley access to property

Grvl Gravel

Pave Paved

NA No alley access

LotShape: General shape of property

Reg Regular

IR1 Slightly irregular

IR2 Moderately Irregular

IR3 Irregular

LandContour: Flatness of the property

Lvl Near Flat/Level

Bnk Banked - Quick and significant rise from street grade to building

HLS Hillside - Significant slope from side to side

Low Depression

Utilities: Type of utilities available

AllPub All public Utilities (E,G,W,& S)

NoSewr Electricity, Gas, and Water (Septic Tank)

NoSeWa Electricity and Gas Only

ELO Electricity only

LotConfig: Lot configuration

Inside Inside lot

Corner Corner lot

CulDSac Cul-de-sac

FR2 Frontage on 2 sides of property

FR3 Frontage on 3 sides of property

LandSlope: Slope of property

Gtl Gentle slope

Mod Moderate Slope

Sev Severe Slope

Neighborhood: Physical locations within Ames city limits

Blmngtn Bloomington Heights

Blueste Bluestem

BrDale Briardale

BrkSide Brookside

ClearCr Clear Creek

CollgCr College Creek

Crawfor Crawford

Edwards Edwards

Gilbert Gilbert

IDOTRR Iowa DOT and Rail Road

MeadowV Meadow Village

Mitchel Mitchell

Names North Ames

NoRidge Northridge

NPkVill Northpark Villa

NridgHt Northridge Heights

NWAmes Northwest Ames

OldTown Old Town

SWISU South & West of Iowa State University

Sawyer Sawyer

SawyerW Sawyer West

Somerst Somerset

StoneBr Stone Brook

Timber Timberland

Veenker Veenker

Condition1: Proximity to various conditions

Artery Adjacent to arterial street

Feedr Adjacent to feeder street

Norm Normal

RRNn Within 200' of North-South Railroad

RRAn Adjacent to North-South Railroad

PosN Near positive off-site feature--park, greenbelt, etc.

PosA Adjacent to postive off-site feature

RRNe Within 200' of East-West Railroad

RRAe Adjacent to East-West Railroad

Condition2: Proximity to various conditions (if more than one is present)

Artery Adjacent to arterial street

Feedr Adjacent to feeder street

Norm Normal

RRNn Within 200' of North-South Railroad

RRAn Adjacent to North-South Railroad

PosN Near positive off-site feature--park, greenbelt, etc.

PosA Adjacent to postive off-site feature

RRNe Within 200' of East-West Railroad

RRAe Adjacent to East-West Railroad

BldgType: Type of dwelling

1Fam Single-family Detached

2FmCon Two-family Conversion; originally built as one-family dwelling

Duplx Duplex

TwnhsE Townhouse End Unit

TwnhsI Townhouse Inside Unit

HouseStyle: Style of dwelling

1Story One story

1.5Fin One and one-half story: 2nd level finished

1.5Unf One and one-half story: 2nd level unfinished

2Story Two story

2.5Fin Two and one-half story: 2nd level finished

2.5Unf Two and one-half story: 2nd level unfinished

SFoyer Split Foyer

SLvl Split Level

OverallQual: Rates the overall material and finish of the house

10 Very Excellent

9 Excellent

8 Very Good

7 Good

6 Above Average

5 Average

4 Below Average

3 Fair

2 Poor

1 Very Poor

OverallCond: Rates the overall condition of the house

10 Very Excellent

9 Excellent

8 Very Good

7 Good

6 Above Average

5 Average

4 Below Average

3 Fair

2 Poor

1 Very Poor

YearBuilt: Original construction date

YearRemodAdd: Remodel date (same as construction date if no remodeling or additions)

RoofStyle: Type of roof

Flat Flat

Gable Gable

Gambrel Gabrel (Barn)

Hip Hip

Mansard Mansard

Shed Shed

RoofMatl: Roof material

ClyTile Clay or Tile

CompShg Standard (Composite) Shingle

Membran Membrane

Metal Metal

Roll Roll

Tar&Grv Gravel & Tar

WdShake Wood Shakes

WdShngl Wood Shingles

Exterior1st: Exterior covering on house

AsbShng Asbestos Shingles

AsphShn Asphalt Shingles

BrkComm Brick Common

BrkFace Brick Face

CBlock Cinder Block

CemntBd Cement Board

HdBoard Hard Board

ImStucc Imitation Stucco

MetalSd Metal Siding

Other Other

Plywood Plywood

PreCast PreCast

Stone Stone

Stucco Stucco

VinylSd Vinyl Siding

Wd Sdng Wood Siding

WdShing Wood Shingles

Exterior2nd: Exterior covering on house (if more than one material)

AsbShng Asbestos Shingles

AsphShn Asphalt Shingles

BrkComm Brick Common

BrkFace Brick Face

CBlock Cinder Block

CemntBd Cement Board

HdBoard Hard Board

ImStucc Imitation Stucco

MetalSd Metal Siding

Other Other

Plywood Plywood

PreCast PreCast

Stone Stone

Stucco Stucco

VinylSd Vinyl Siding

Wd Sdng Wood Siding

WdShing Wood Shingles

MasVnrType: Masonry veneer type

BrkCmn Brick Common

BrkFace Brick Face

CBlock Cinder Block

None None

Stone Stone

MasVnrArea: Masonry veneer area in square feet

ExterQual: Evaluates the quality of the material on the exterior

Ex Excellent

Gd Good

TA Average/Typical

Fa Fair

Po Poor

ExterCond: Evaluates the present condition of the material on the exterior

Ex Excellent

Gd Good

TA Average/Typical

Fa Fair

Po Poor

Foundation: Type of foundation

BrkTil Brick & Tile

CBlock Cinder Block

PConc Poured Contrete

Slab Slab

Stone Stone

Wood Wood

BsmtQual: Evaluates the height of the basement

Ex Excellent (100+ inches)

Gd Good (90-99 inches)

TA Typical (80-89 inches)

Fa Fair (70-79 inches)

Po Poor (<70 inches

NA No Basement

BsmtCond: Evaluates the general condition of the basement

Ex Excellent

Gd Good

TA Typical - slight dampness allowed

Fa Fair - dampness or some cracking or settling

Po Poor - Severe cracking, settling, or wetness

NA No Basement

BsmtExposure: Refers to walkout or garden level walls

Gd Good Exposure

Av Average Exposure (split levels or foyers typically score average or above)

Mn Mimimum Exposure

No No Exposure

NA No Basement

BsmtFinType1: Rating of basement finished area

GLQ Good Living Quarters

ALQ Average Living Quarters

BLQ Below Average Living Quarters

Rec Average Rec Room

LwQ Low Quality

Unf Unfinshed

NA No Basement

BsmtFinSF1: Type 1 finished square feet

BsmtFinType2: Rating of basement finished area (if multiple types)

GLQ Good Living Quarters

ALQ Average Living Quarters

BLQ Below Average Living Quarters

Rec Average Rec Room

LwQ Low Quality

Unf Unfinshed

NA No Basement

BsmtFinSF2: Type 2 finished square feet

BsmtUnfSF: Unfinished square feet of basement area

TotalBsmtSF: Total square feet of basement area

Heating: Type of heating

Floor Floor Furnace

GasA Gas forced warm air furnace

GasW Gas hot water or steam heat

Grav Gravity furnace

OthW Hot water or steam heat other than gas

Wall Wall furnace

HeatingQC: Heating quality and condition

Ex Excellent

Gd Good

TA Average/Typical

Fa Fair

Po Poor

CentralAir: Central air conditioning

N No

Y Yes

Electrical: Electrical system

SBrkr Standard Circuit Breakers & Romex

FuseA Fuse Box over 60 AMP and all Romex wiring (Average)

FuseF 60 AMP Fuse Box and mostly Romex wiring (Fair)

FuseP 60 AMP Fuse Box and mostly knob & tube wiring (poor)

Mix Mixed

1stFlrSF: First Floor square feet

2ndFlrSF: Second floor square feet

LowQualFinSF: Low quality finished square feet (all floors)

GrLivArea: Above grade (ground) living area square feet

BsmtFullBath: Basement full bathrooms

BsmtHalfBath: Basement half bathrooms

FullBath: Full bathrooms above grade

HalfBath: Half baths above grade

Bedroom: Bedrooms above grade (does NOT include basement bedrooms)

Kitchen: Kitchens above grade

KitchenQual: Kitchen quality

Ex Excellent

Gd Good

TA Typical/Average

Fa Fair

Po Poor

TotRmsAbvGrd: Total rooms above grade (does not include bathrooms)

Functional: Home functionality (Assume typical unless deductions are warranted)

Typ Typical Functionality

Min1 Minor Deductions 1

Min2 Minor Deductions 2

Mod Moderate Deductions

Maj1 Major Deductions 1

Maj2 Major Deductions 2

Sev Severely Damaged

Sal Salvage only

Fireplaces: Number of fireplaces

FireplaceQu: Fireplace quality

Ex Excellent - Exceptional Masonry Fireplace

Gd Good - Masonry Fireplace in main level

TA Average - Prefabricated Fireplace in main living area or Masonry Fireplace in basement

Fa Fair - Prefabricated Fireplace in basement

Po Poor - Ben Franklin Stove

NA No Fireplace

GarageType: Garage location

2Types More than one type of garage

Attchd Attached to home

Basment Basement Garage

BuiltIn Built-In (Garage part of house - typically has room above garage)

CarPort Car Port

Detchd Detached from home

NA No Garage

GarageYrBlt: Year garage was built

GarageFinish: Interior finish of the garage

Fin Finished

RFn Rough Finished

Unf Unfinished

NA No Garage

GarageCars: Size of garage in car capacity

GarageArea: Size of garage in square feet

GarageQual: Garage quality

Ex Excellent

Gd Good

TA Typical/Average

Fa Fair

Po Poor

NA No Garage

GarageCond: Garage condition

Ex Excellent

Gd Good

TA Typical/Average

Fa Fair

Po Poor

NA No Garage

PavedDrive: Paved driveway

Y Paved

P Partial Pavement

N Dirt/Gravel

WoodDeckSF: Wood deck area in square feet

OpenPorchSF: Open porch area in square feet

EnclosedPorch: Enclosed porch area in square feet

3SsnPorch: Three season porch area in square feet

ScreenPorch: Screen porch area in square feet

PoolArea: Pool area in square feet

PoolQC: Pool quality

Ex Excellent

Gd Good

TA Average/Typical

Fa Fair

NA No Pool

Fence: Fence quality

GdPrv Good Privacy

MnPrv Minimum Privacy

GdWo Good Wood

MnWw Minimum Wood/Wire

NA No Fence

MiscFeature: Miscellaneous feature not covered in other categories

Elev Elevator

Gar2 2nd Garage (if not described in garage section)

Othr Other

Shed Shed (over 100 SF)

TenC Tennis Court

NA None

MiscVal: $Value of miscellaneous feature

MoSold: Month Sold (MM)

YrSold: Year Sold (YYYY)

SaleType: Type of sale

WD Warranty Deed - Conventional

CWD Warranty Deed - Cash

VWD Warranty Deed - VA Loan

New Home just constructed and sold

COD Court Officer Deed/Estate

Con Contract 15% Down payment regular terms

ConLw Contract Low Down payment and low interest

ConLI Contract Low Interest

ConLD Contract Low Down

Oth Other

SaleCondition: Condition of sale

Normal Normal Sale

Abnorml Abnormal Sale - trade, foreclosure, short sale

AdjLand Adjoining Land Purchase

Alloca Allocation - two linked properties with separate deeds, typically condo with a garage unit

Family Sale between family members

Partial Home was not completed when last assessed (associated with New Homes)

# Let's load the house prices dataset

df_train = pd.read_csv('house_prices.csv')

#check the decoration

df_train.columns

Index(['Id', 'MSSubClass', 'MSZoning', 'LotFrontage', 'LotArea', 'Street',

'Alley', 'LotShape', 'LandContour', 'Utilities', 'LotConfig',

'LandSlope', 'Neighborhood', 'Condition1', 'Condition2', 'BldgType',

'HouseStyle', 'OverallQual', 'OverallCond', 'YearBuilt', 'YearRemodAdd',

'RoofStyle', 'RoofMatl', 'Exterior1st', 'Exterior2nd', 'MasVnrType',

'MasVnrArea', 'ExterQual', 'ExterCond', 'Foundation', 'BsmtQual',

'BsmtCond', 'BsmtExposure', 'BsmtFinType1', 'BsmtFinSF1',

'BsmtFinType2', 'BsmtFinSF2', 'BsmtUnfSF', 'TotalBsmtSF', 'Heating',

'HeatingQC', 'CentralAir', 'Electrical', '1stFlrSF', '2ndFlrSF',

'LowQualFinSF', 'GrLivArea', 'BsmtFullBath', 'BsmtHalfBath', 'FullBath',

'HalfBath', 'BedroomAbvGr', 'KitchenAbvGr', 'KitchenQual',

'TotRmsAbvGrd', 'Functional', 'Fireplaces', 'FireplaceQu', 'GarageType',

'GarageYrBlt', 'GarageFinish', 'GarageCars', 'GarageArea', 'GarageQual',

'GarageCond', 'PavedDrive', 'WoodDeckSF', 'OpenPorchSF',

'EnclosedPorch', '3SsnPorch', 'ScreenPorch', 'PoolArea', 'PoolQC',

'Fence', 'MiscFeature', 'MiscVal', 'MoSold', 'YrSold', 'SaleType',

'SaleCondition', 'SalePrice'],

dtype='object')

Understand the data#

In order to understand our data, we can look at each variable and try to understand their meaning and relevance to this problem.

It is time-consuming, but it will give us the flavour of our dataset.

In order to have some discipline in our analysis, we can create an Excel spreadsheet with the following columns:

Variable - Variable name.

Type - Identification of the variables’ type. There are two possible values for this field: ‘numerical’ or ‘categorical’. By ‘numerical’ we mean variables for which the values are numbers, and by ‘categorical’ we mean variables for which the values are categories.

Segment - Identification of the variables’ segment. We can define three possible segments: building, space or location. When we say ‘building’, we mean a variable that relates to the physical characteristics of the building (e.g. ‘OverallQual’). When we say ‘space’, we mean a variable that reports space properties of the house (e.g. ‘TotalBsmtSF’). Finally, when we say a ‘location’, we mean a variable that gives information about the place where the house is located (e.g. ‘Neighborhood’).

Expectation - Our expectation about the variable influence in ‘SalePrice’. We can use a categorical scale with ‘High’, ‘Medium’ and ‘Low’ as possible values.

Conclusion - Our conclusions about the importance of the variable, after we give a quick look at the data. We can keep with the same categorical scale as in ‘Expectation’.

Comments - Any general comments that occured to us.

While ‘Type’ and ‘Segment’ is just for possible future reference, the column ‘Expectation’ is important because it will help us develop a ‘sixth sense’. To fill this column, we should read the description of all the variables and, one by one, ask ourselves:

Do we think about this variable when we are buying a house? (e.g. When we think about the house of our dreams, do we care about its ‘Masonry veneer type’?).

If so, how important would this variable be? (e.g. What is the impact of having ‘Excellent’ material on the exterior instead of ‘Poor’? And of having ‘Excellent’ instead of ‘Good’?).

Is this information already described in any other variable? (e.g. If ‘LandContour’ gives the flatness of the property, do we really need to know the ‘LandSlope’?).

After this daunting exercise, we can filter the spreadsheet and look carefully to the variables with ‘High’ ‘Expectation’. Then, we can rush into some scatter plots between those variables and ‘SalePrice’, filling in the ‘Conclusion’ column which is just the correction of our expectations.

I went through this process and concluded that the following variables can play an important role in this problem:

OverallQual

YearBuilt.

TotalBsmtSF.

GrLivArea.

I ended up with two ‘building’ variables (‘OverallQual’ and ‘YearBuilt’) and two ‘space’ variables (‘TotalBsmtSF’ and ‘GrLivArea’).

This might be a little bit unexpected as it goes against the real estate mantra that all that matters is ‘location, location and location’.

It is possible that this quick data examination process was a bit harsh for categorical variables. For example, I expected the ‘Neigborhood’ variable to be more relevant, but after the data examination I ended up excluding it. Maybe this is related to the use of scatter plots instead of boxplots, which are more suitable for categorical variables visualization. The way we visualize data often influences our conclusions.

However, the main point of this exercise was to think a little about our data and expectactions, so I think we achieved our goal. Now it’s time for ‘a little less conversation, a little more action please’. Let’s shake it!

Subjective analysis#

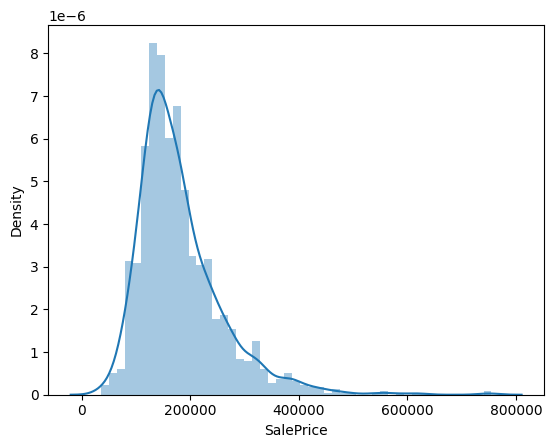

‘SalePrice’ is the reason of our quest. first we will do some descriptive analysis, which will help us to understand the distribution of the data

#descriptive statistics summary

df_train['SalePrice'].describe()

count 1460.000000

mean 180921.195890

std 79442.502883

min 34900.000000

25% 129975.000000

50% 163000.000000

75% 214000.000000

max 755000.000000

Name: SalePrice, dtype: float64

#histogram

sns.distplot(df_train['SalePrice']);

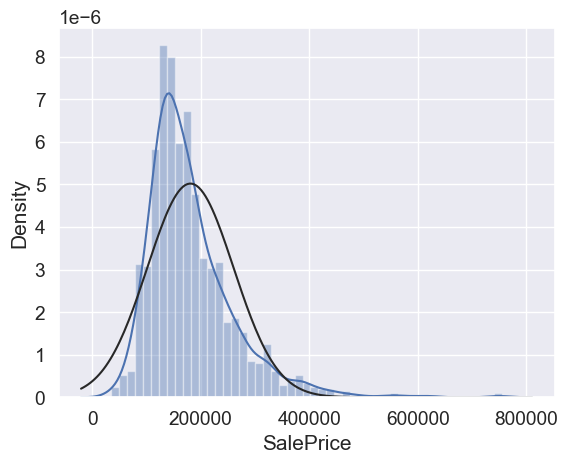

From above plot we can see that:

Deviate from the normal distribution.

Have appreciable positive skewness.

Show peakedness.

Skewness and kurtosis

Skewness is a measure of the asymmetry of the data distribution. It tells us about the direction of the outliers. If the skewness is negative, the tail is on the left side of the distribution and if it is positive, the tail is on the right side.

Kurtosis is a measure of the “tailedness” of the data distribution. It tells us about the outliers of the data distribution. If the kurtosis is high, the data distribution has heavy tails and the outliers are more spread out. If the kurtosis is low, the data distribution has light tails and the outliers are more concentrated.

Skewness and kurtosis are important because they help us understand the shape of the data distribution and the presence of outliers.

#skewness and kurtosis

print("Skewness: %f" % df_train['SalePrice'].skew())

print("Kurtosis: %f" % df_train['SalePrice'].kurt())

Skewness: 1.882876

Kurtosis: 6.536282

What does the abovve number mean?

Skewness: 1.882876

Kurtosis: 6.529276

A value of 0 indicates a normal distribution,

while positive values indicate a right-skewed distribution and

negative values indicate a left-skewed distribution.

In this case, the skewness value of 1.882876 indicates that the ‘SalePrice’ distribution is moderately right-skewed. This means that there are more values on the left side of the distribution and fewer values on the right side.

The kurtosis value of 6.529276 indicates that the distribution is more peaked (leptokurtic) than a normal distribution, which suggests the presence of outliers or extreme values in the data.

Releationship of ‘SalePrice’ with other variables#

Relationship with numerical variables#

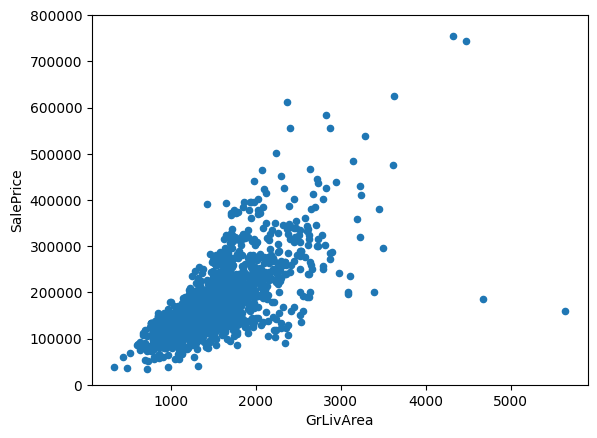

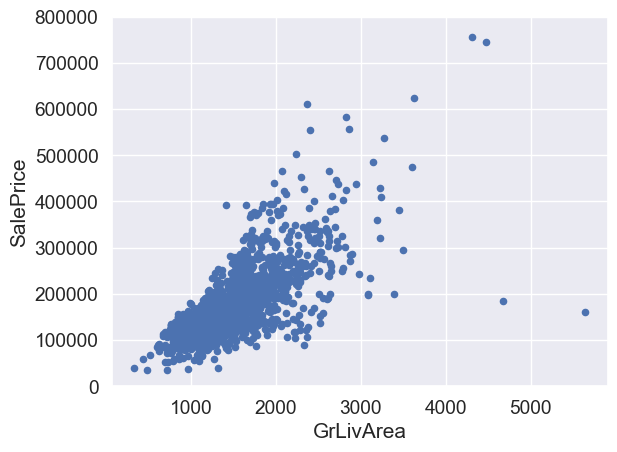

#scatter plot grlivarea/saleprice

var = 'GrLivArea'

data = pd.concat([df_train['SalePrice'], df_train[var]], axis=1)

data.plot.scatter(x=var, y='SalePrice', ylim=(0,800000));

‘SalePrice’ and ‘GrLivArea’ follow a linear relationship.

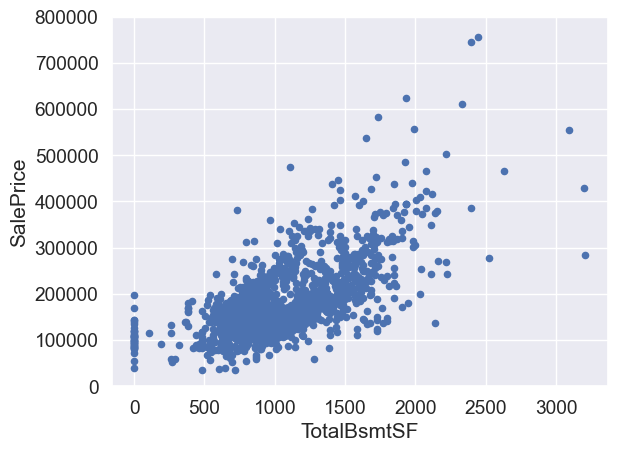

Let’s check the relationship between ‘SalePrice’ and ‘TotalBsmtSF’.

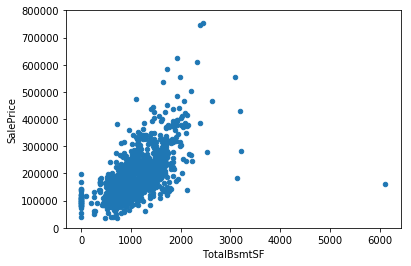

#scatter plot totalbsmtsf/saleprice

var = 'TotalBsmtSF'

data = pd.concat([df_train['SalePrice'], df_train[var]], axis=1)

data.plot.scatter(x=var, y='SalePrice', ylim=(0,800000));

‘TotalBsmtSF’ also has a strong relationship with ‘SalePrice’ which can be an exponential or a strong linear relationship.

Relationship with categorical features#

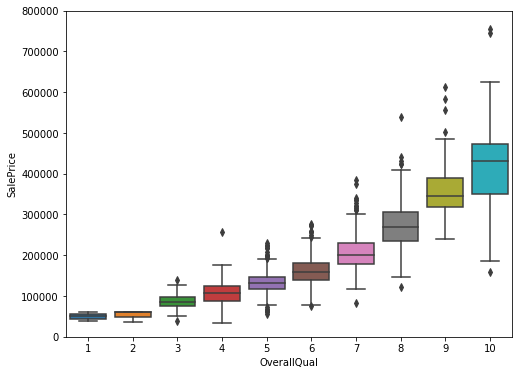

#box plot overallqual/saleprice

var = 'OverallQual'

data = pd.concat([df_train['SalePrice'], df_train[var]], axis=1)

f, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 6))

fig = sns.boxplot(x=var, y="SalePrice", data=data)

fig.axis(ymin=0, ymax=800000);

Above plot shows that as the Overall quality of the house increases as the Sale price increases, which makes sense.

The box plot is a good way to compare the distribution of the Sale price for different levels of Overall quality.

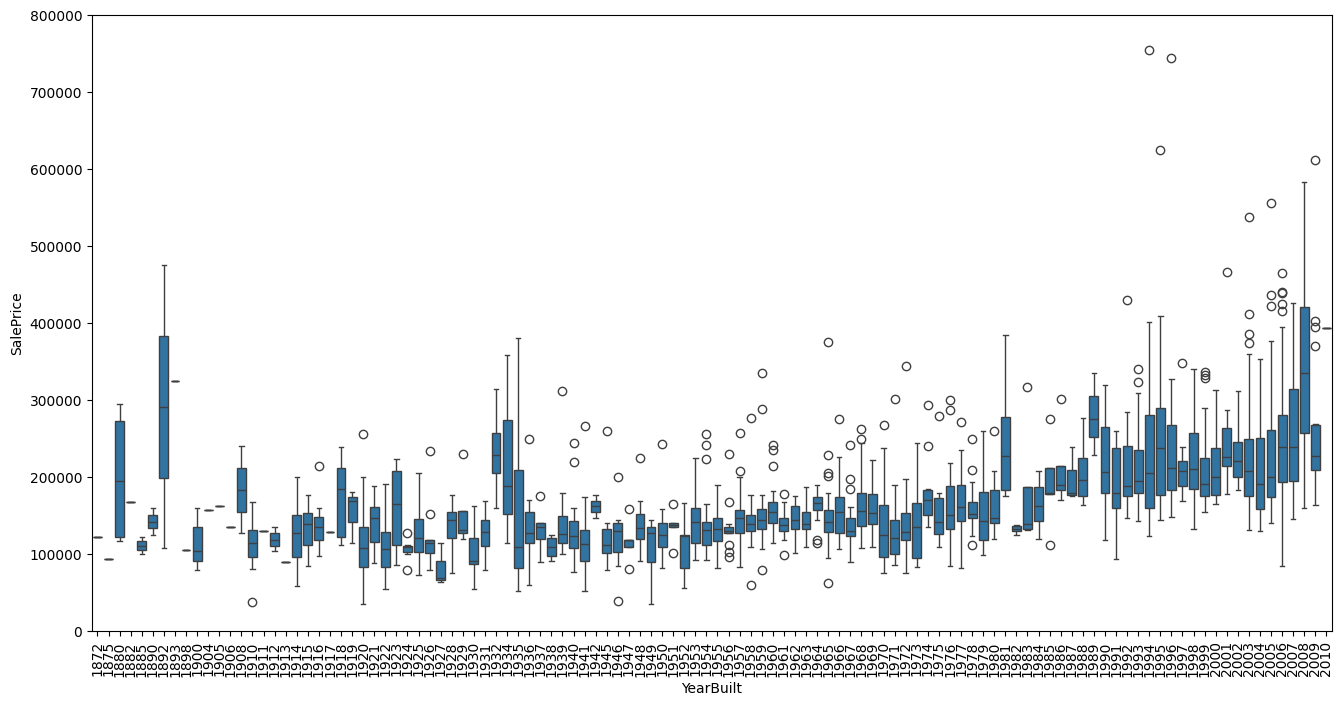

Let’s do the same for ‘YearBuilt’

var = 'YearBuilt'

data = pd.concat([df_train['SalePrice'], df_train[var]], axis=1)

f, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(16, 8))

fig = sns.boxplot(x=var, y="SalePrice", data=data)

fig.axis(ymin=0, ymax=800000);

plt.xticks(rotation=90);

Although not strongly but ‘SalePrice’ is more prone to spend more money in new stuff than in old relics.

Note: we don’t know if ‘SalePrice’ is in constant prices. Constant prices try to remove the effect of inflation. If ‘SalePrice’ is not in constant prices, it should be, so than prices are comparable over the years.

In summary#

Here ,we can conclude that:

‘GrLivArea’ and ‘TotalBsmtSF’ seem to be linearly related with ‘SalePrice’. Both relationships are positive, which means that as one variable increases, the other also increases.

In the case of ‘TotalBsmtSF’, we can see that the slope of the linear relationship is particularly high.

‘OverallQual’ and ‘YearBuilt’ also seem to be related with ‘SalePrice’. The relationship seems to be stronger in the case of ‘OverallQual’, where the box plot shows how sales prices increase with the overall quality.

We just analysed four variables, but there are many other that we should analyse. The trick here seems to be the choice of the right features (feature selection) and not the definition of complex relationships between them (feature engineering).

Objective analysis#

Until now we just followed our intuition and analysed the variables we thought were important. In spite of our efforts to give an objective character to our analysis, we must say that our starting point was subjective.

So, let’s overcome inertia and do a more objective analysis.

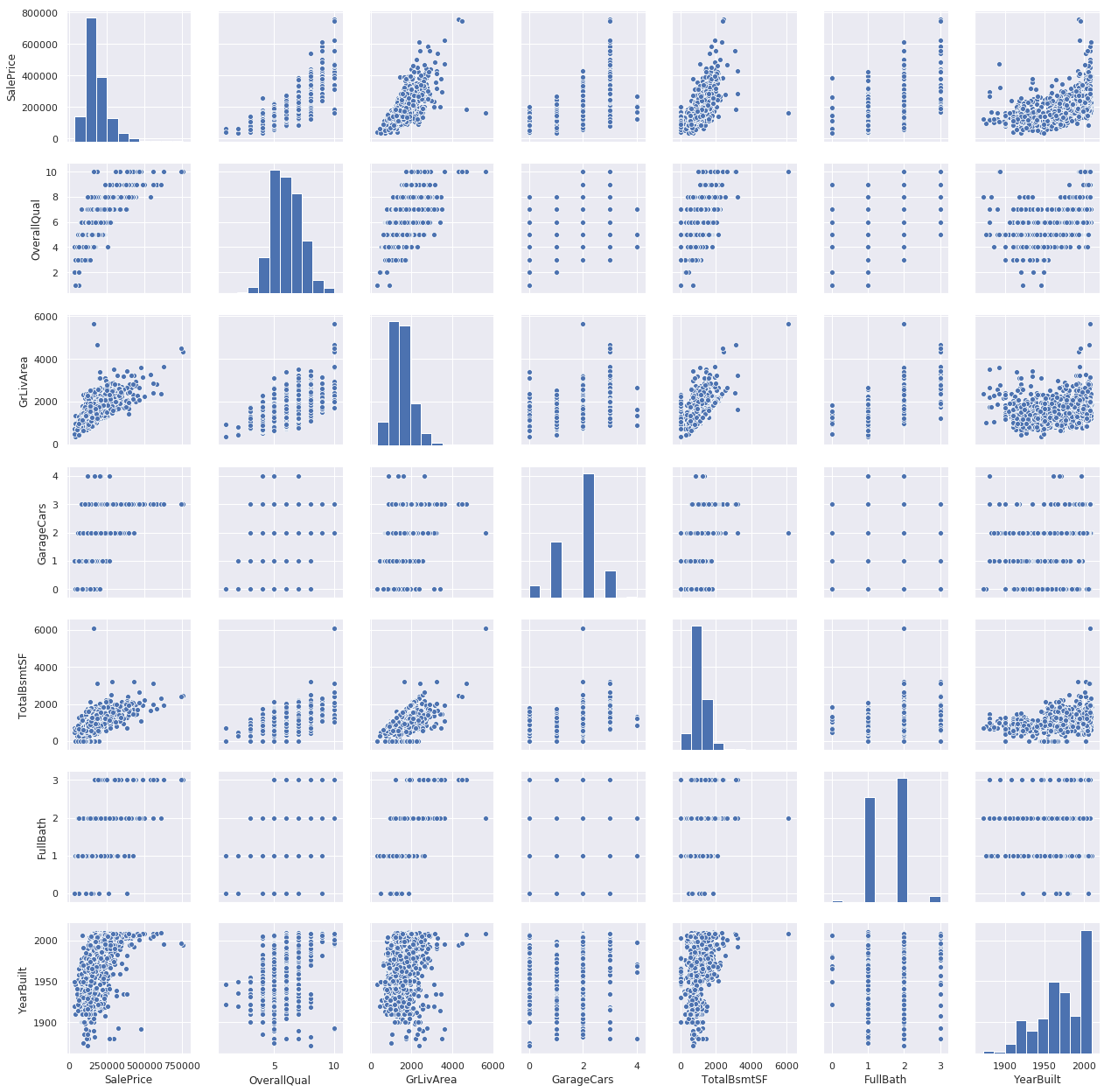

Correlation analysis#

To understand the relationship objectively for all sort of variables, we can do some correlation analysis.

Correlation matrix (heatmap style).

‘SalePrice’ correlation matrix (zoomed heatmap style).

Scatter plots between the most correlated variables (move like Jagger style).

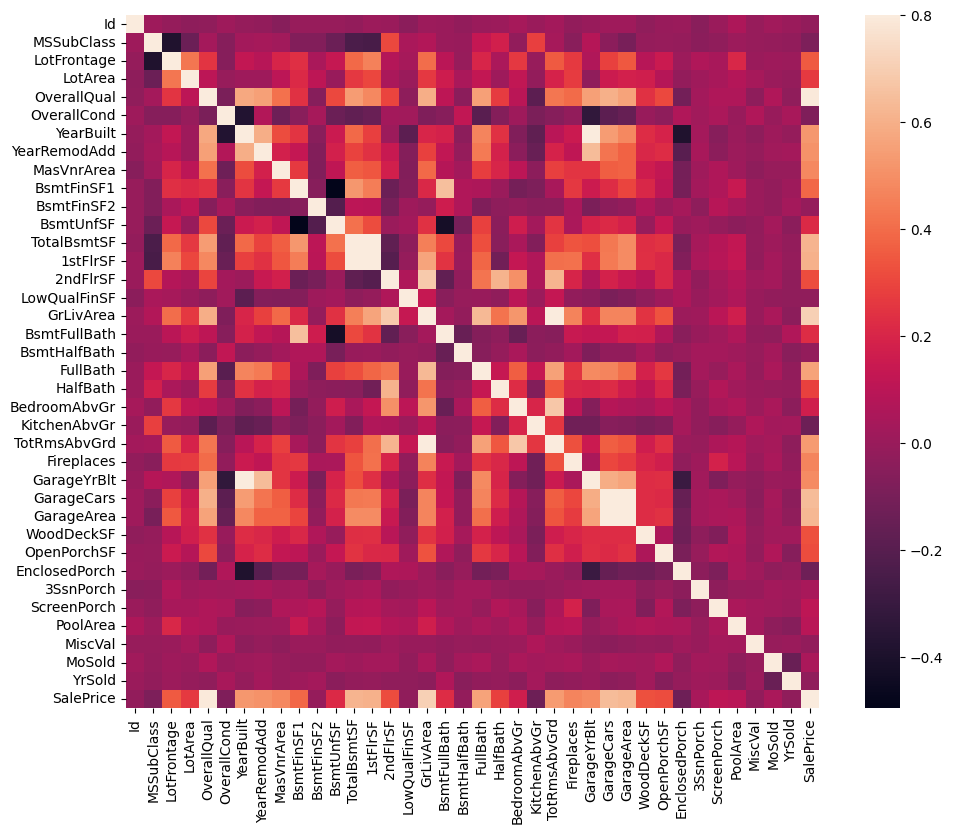

Correlation matrix (heatmap style)#

#correlation matrix

numeric_features = df_train.select_dtypes(include=[np.number]).columns

corrmat = df_train[numeric_features].corr()

f, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(12, 9))

sns.heatmap(corrmat, vmax=.8, square=True)

<Axes: >

Heatmap is the best way to get a quick overview of the correlation matrix for all the variables.

At first sight, there are two red colored squares that get my attention.

The first one refers to the ‘TotalBsmtSF’ and ‘1stFlrSF’ variables, and

‘GarageX’ variables.

Both cases show how significant the correlation is between these variables. Actually, this correlation is so strong that it can indicate a situation of multicollinearity.

If we think about these variables, we can conclude that they give almost the same information so multicollinearity really occurs.

Heatmaps are great to detect this kind of situations and in problems dominated by feature selection, like ours, they are an essential tool.

Another thing that got my attention was the ‘SalePrice’ correlations. We can see our well-known ‘GrLivArea’, ‘TotalBsmtSF’, and ‘OverallQual’,

But we can also see many other variables that should be taken into account. That’s what we will do next.

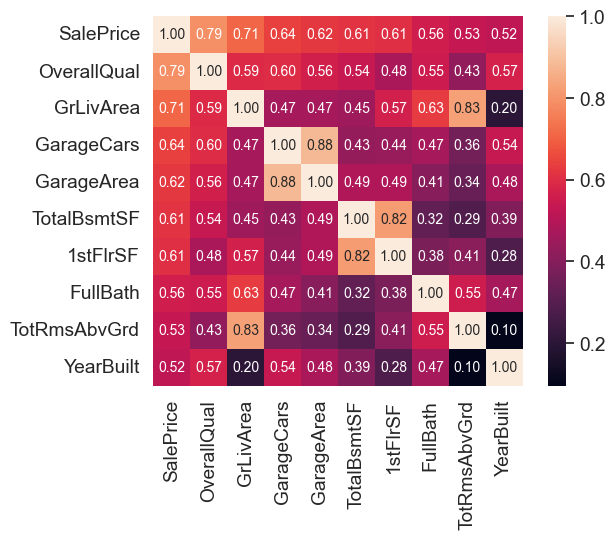

‘SalePrice’ correlation matrix#

#saleprice correlation matrix

k = 10 #number of variables for heatmap

# Get the correlation matrix for the top k variables

cols = corrmat.nlargest(k, 'SalePrice')['SalePrice'].index

cm = np.corrcoef(df_train[cols].values.T)

sns.set(font_scale=1.25)

hm = sns.heatmap(cm, cbar=True, annot=True, square=True, fmt='.2f', annot_kws={'size': 10}, yticklabels=cols.values, xticklabels=cols.values)

plt.show()

These are the variables most correlated with ‘SalePrice’

👉 ‘OverallQual’, ‘GrLivArea’ and ‘TotalBsmtSF’ are strongly correlated with ‘SalePrice’.

👉 ‘GarageCars’ and ‘GarageArea’ are also some of the most strongly correlated variables.

However, as we discussed in the last sub-point, the number of cars that fit into the garage is a consequence of the garage area.

‘GarageCars’ and ‘GarageArea’ are like twin brothers. You’ll never be able to distinguish them.

Therefore, we just need one of these variables in our analysis (we can keep ‘GarageCars’ since its correlation with ‘SalePrice’ is higher).

👉 ‘TotalBsmtSF’ and ‘1stFloor’ also seem to be twin brothers. - We can keep ‘TotalBsmtSF’ just to say that our first guess was right

👉 ‘FullBath’

👉 ‘TotRmsAbvGrd’ and ‘GrLivArea’, twin brothers again.

👉 ‘YearBuilt’… It seems that ‘YearBuilt’ is slightly correlated with ‘SalePrice’.

Let’s proceed to the scatter plots.

Missing data#

Important questions when thinking about missing data:

How prevalent is the missing data?

Is missing data random or does it have a pattern?

The answer to these questions is important for practical reasons because missing data can imply a reduction of the sample size. This can prevent us from proceeding with the analysis. Moreover, from a substantive perspective, we need to ensure that the missing data process is not biased and hidding an inconvenient truth.

#missing data

total = df_train.isnull().sum().sort_values(ascending=False)

percent = (df_train.isnull().sum()/df_train.isnull().count()).sort_values(ascending=False)

missing_data = pd.concat([total, percent], axis=1, keys=['Total', 'Percent'])

missing_data.head(20)

| Total | Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| PoolQC | 1453 | 0.995205 |

| MiscFeature | 1406 | 0.963014 |

| Alley | 1369 | 0.937671 |

| Fence | 1179 | 0.807534 |

| MasVnrType | 872 | 0.597260 |

| FireplaceQu | 690 | 0.472603 |

| LotFrontage | 259 | 0.177397 |

| GarageYrBlt | 81 | 0.055479 |

| GarageCond | 81 | 0.055479 |

| GarageType | 81 | 0.055479 |

| GarageFinish | 81 | 0.055479 |

| GarageQual | 81 | 0.055479 |

| BsmtFinType2 | 38 | 0.026027 |

| BsmtExposure | 38 | 0.026027 |

| BsmtQual | 37 | 0.025342 |

| BsmtCond | 37 | 0.025342 |

| BsmtFinType1 | 37 | 0.025342 |

| MasVnrArea | 8 | 0.005479 |

| Electrical | 1 | 0.000685 |

| Id | 0 | 0.000000 |

Let’s analyse this to understand how to handle the missing data.

👉 We’ll consider that when more than 15% of the data is missing, we should delete the corresponding variable and pretend it never existed. This means that we will not try any trick to fill the missing data in these cases.

👉 There is a set of variables (e.g. ‘PoolQC’, ‘MiscFeature’, ‘Alley’, etc.) that we should delete. None of these variables seem to be very important, since most of them are not aspects in which we think about when buying a house (maybe that’s the reason why data is missing?).

👉 Variables like ‘PoolQC’, ‘MiscFeature’ and ‘FireplaceQu’ are strong candidates for outliers, so we’ll be happy to delete them.

👉 For other cases, we can see that ‘GarageX’ variables have the same number of missing data. I bet missing data refers to the same set of observations (although I will not check it; it’s just 5%). Since the most important information regarding garages is expressed by ‘GarageCars’ and considering that we are just talking about 5% of missing data, I’ll delete the mentioned ‘GarageX’ variables. The same logic applies to ‘BsmtX’ variables.

👉 Regarding ‘MasVnrArea’ and ‘MasVnrType’, we can consider that these variables are not essential. Furthermore, they have a strong correlation with ‘YearBuilt’ and ‘OverallQual’ which are already considered. Thus, we will not lose information if we delete ‘MasVnrArea’ and ‘MasVnrType’.

👉 Finally, we have one missing observation in ‘Electrical’. Since it is just one observation, we’ll delete this observation and keep the variable.

In summary, to handle missing data, we’ll delete all the variables with missing data, except the variable ‘Electrical’. In ‘Electrical’ we’ll just delete the observation with missing data.

#dealing with missing data

df_train = df_train.drop(columns=(missing_data[missing_data['Total'] > 1]).index)

df_train = df_train.drop(df_train.loc[df_train['Electrical'].isnull()].index)

df_train.isnull().sum().max() #just checking that there's no missing data missing...

0

Outliers#

Outliers is also something that we should be aware of. Why? Because outliers can markedly affect our models and can be a valuable source of information, providing us insights about specific behaviours.

Outliers is a complex subject and it deserves more attention. Here, we’ll just do a quick analysis through the standard deviation of ‘SalePrice’ and a set of scatter plots.

Univariate analysis#

The primary concern here is to establish a threshold that defines an observation as an outlier. To do so, we’ll standardize the data. In this context, data standardization means converting data values to have mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1.

#standardizing data

saleprice_scaled = StandardScaler().fit_transform(df_train['SalePrice'].values.reshape(-1, 1))

low_range = saleprice_scaled[saleprice_scaled.ravel().argsort()][:10]

high_range = saleprice_scaled[saleprice_scaled.ravel().argsort()][-10:]

print('outer range (low) of the distribution:')

print(low_range)

print('\nouter range (high) of the distribution:')

print(high_range)

outer range (low) of the distribution:

[[-1.83820775]

[-1.83303414]

[-1.80044422]

[-1.78282123]

[-1.77400974]

[-1.62295562]

[-1.6166617 ]

[-1.58519209]

[-1.58519209]

[-1.57269236]]

outer range (high) of the distribution:

[[3.82758058]

[4.0395221 ]

[4.49473628]

[4.70872962]

[4.728631 ]

[5.06034585]

[5.42191907]

[5.58987866]

[7.10041987]

[7.22629831]]

How ‘SalePrice’ looks with her new clothes:

Low range values are similar and not too far from 0.

High range values are far from 0 and the 7.something values are really out of range.

For now, we’ll not consider any of these values as an outlier but we should be careful with those two 7.something values.

Bivariate analysis#

We already know the following scatter plots by heart. However, when we look to things from a new perspective, there’s always something to discover.

#bivariate analysis saleprice/grlivarea

var = 'GrLivArea'

data = pd.concat([df_train['SalePrice'], df_train[var]], axis=1)

data.plot.scatter(x=var, y='SalePrice', ylim=(0,800000));

What has been revealed:

👉 The two values with bigger ‘GrLivArea’ seem strange and they are not following the crowd. We can speculate why this is happening. These two points are not representative of the typical case. Therefore, we’ll define them as outliers and delete them.

👉 The two observations in the top of the plot are those 7.something observations that we said we should be careful about. They look like two special cases, however they seem to be following the trend. For that reason, we will keep them.

#deleting points

df_train.sort_values(by = 'GrLivArea', ascending = False)[:2]

df_train = df_train.drop(df_train[df_train['Id'] == 1299].index)

df_train = df_train.drop(df_train[df_train['Id'] == 524].index)

#bivariate analysis saleprice/grlivarea

var = 'TotalBsmtSF'

data = pd.concat([df_train['SalePrice'], df_train[var]], axis=1)

data.plot.scatter(x=var, y='SalePrice', ylim=(0,800000));

We can feel tempted to eliminate some observations (e.g. TotalBsmtSF > 3000) but I suppose it’s not worth it. We can live with that, so we’ll not do anything.

Testing assumptions#

Let’s do testing for the assumptions underlying the statistical bases for multivariate analysis. We already did some data cleaning and discovered a lot about ‘SalePrice’. Now it’s time to go deep and understand how ‘SalePrice’ complies with the statistical assumptions that enables us to apply multivariate techniques.

According to Hair et al. (2013), four assumptions should be tested:

Normality - When we talk about normality what we mean is that the data should look like a normal distribution. This is important because several statistic tests rely on this (e.g. t-statistics). In this exercise we’ll just check univariate normality for ‘SalePrice’ (which is a limited approach). Remember that univariate normality doesn’t ensure multivariate normality (which is what we would like to have), but it helps. Another detail to take into account is that in big samples (>200 observations) normality is not such an issue. However, if we solve normality, we avoid a lot of other problems (e.g. heteroscedacity) so that’s the main reason why we are doing this analysis.

Homoscedasticity - Homoscedasticity refers to the ‘assumption that dependent variable(s) exhibit equal levels of variance across the range of predictor variable(s)’ (Hair et al., 2013). Homoscedasticity is desirable because we want the error term to be the same across all values of the independent variables.

Linearity- The most common way to assess linearity is to examine scatter plots and search for linear patterns. If patterns are not linear, it would be worthwhile to explore data transformations. However, we’ll not get into this because most of the scatter plots we’ve seen appear to have linear relationships.

Absence of correlated errors - Correlated errors, like the definition suggests, happen when one error is correlated to another. For instance, if one positive error makes a negative error systematically, it means that there’s a relationship between these variables. This occurs often in time series, where some patterns are time related. We’ll also not get into this. However, if you detect something, try to add a variable that can explain the effect you’re getting. That’s the most common solution for correlated errors.

Normality#

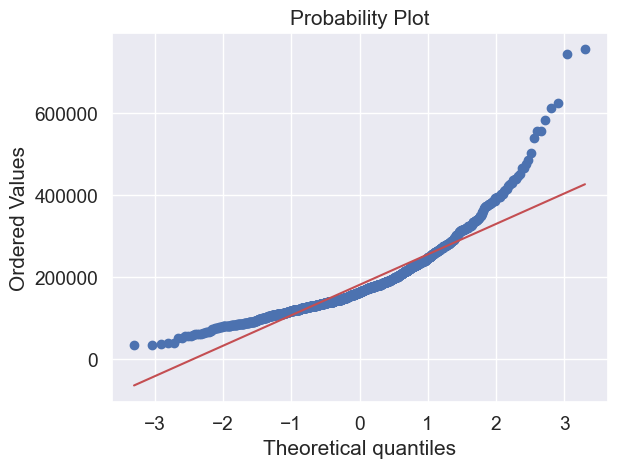

The point here is to test ‘SalePrice’ in a very lean way. We’ll do this paying attention to:

Histogram - Kurtosis and skewness.

Normal probability plot - Data distribution should closely follow the diagonal that represents the normal distribution.

#histogram and normal probability plot

sns.distplot(df_train['SalePrice'], fit=norm);

fig = plt.figure()

res = stats.probplot(df_train['SalePrice'], plot=plt)

Ok, ‘SalePrice’ is not normal. It shows ‘peakedness’, positive skewness and does not follow the diagonal line.

But everything’s not lost. A simple data transformation can solve the problem.

In case of positive skewness, log transformations usually works well.

#applying log transformation

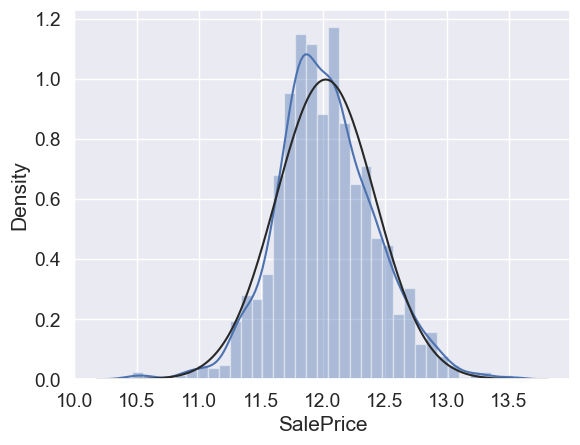

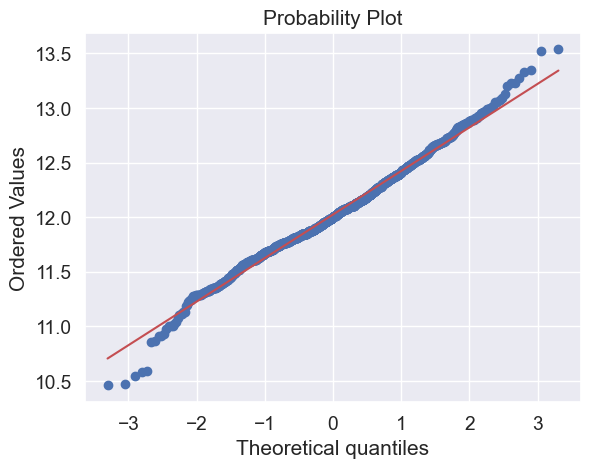

df_train['SalePrice'] = np.log(df_train['SalePrice'])

#transformed histogram and normal probability plot

sns.distplot(df_train['SalePrice'], fit=norm);

fig = plt.figure()

res = stats.probplot(df_train['SalePrice'], plot=plt)

Done! Let’s check what’s going on with ‘GrLivArea’.

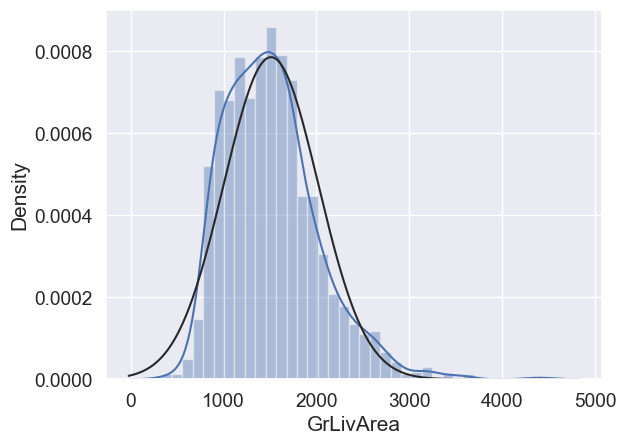

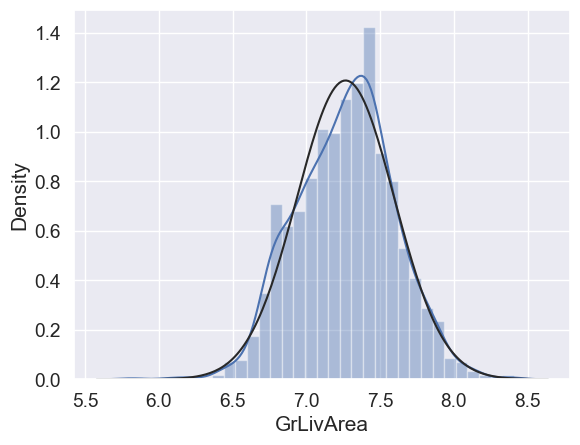

#histogram and normal probability plot

sns.distplot(df_train['GrLivArea'], fit=norm);

fig = plt.figure()

res = stats.probplot(df_train['GrLivArea'], plot=plt)

Skewness

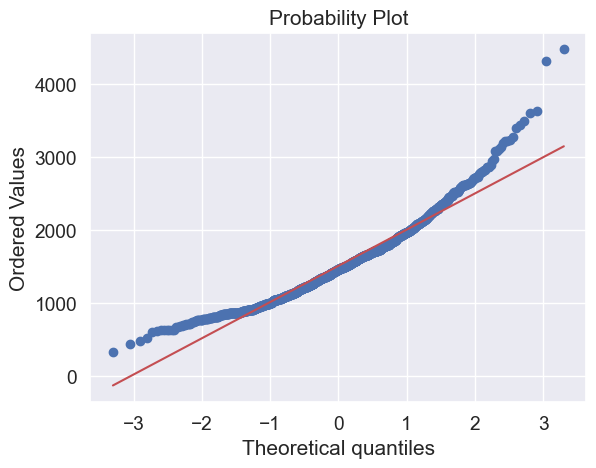

#data transformation

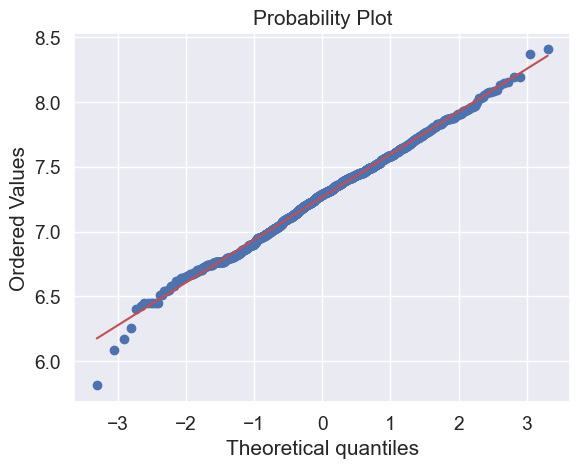

df_train['GrLivArea'] = np.log(df_train['GrLivArea'])

#transformed histogram and normal probability plot

sns.distplot(df_train['GrLivArea'], fit=norm);

fig = plt.figure()

res = stats.probplot(df_train['GrLivArea'], plot=plt)

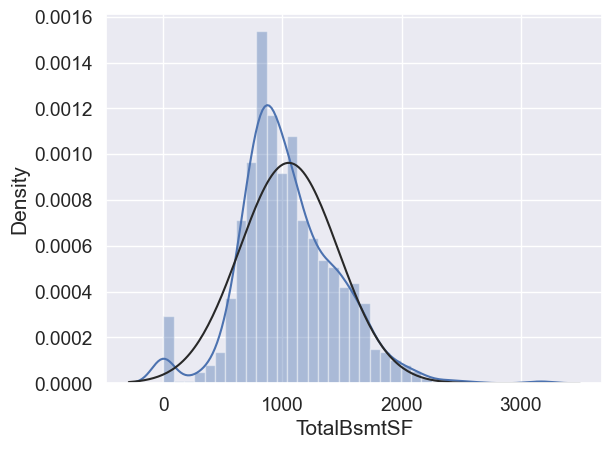

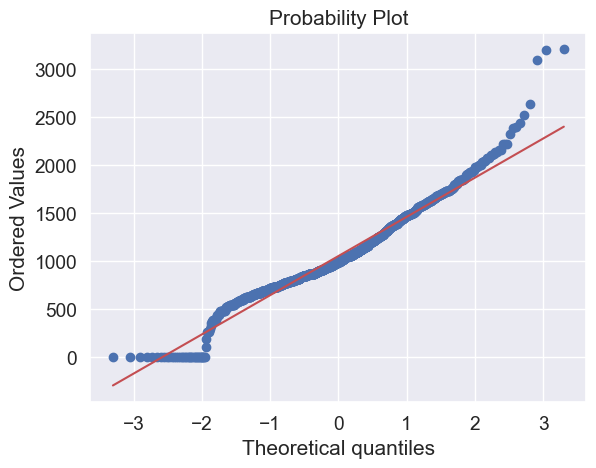

#histogram and normal probability plot

sns.distplot(df_train['TotalBsmtSF'], fit=norm);

fig = plt.figure()

res = stats.probplot(df_train['TotalBsmtSF'], plot=plt)

What do we have here?

Something that, in general, presents skewness.

A significant number of observations with value zero (houses without basement).

A big problem because the value zero doesn’t allow us to do log transformations.

👉 To apply a log transformation here, we’ll create a variable that can get the effect of having or not having basement (binary variable).

👉 Then, we’ll do a log transformation to all the non-zero observations, ignoring those with value zero. This way we can transform data, without losing the effect of having or not basement.

#create column for new variable (one is enough because it's a binary categorical feature)

#if area>0 it gets 1, for area==0 it gets 0

df_train['HasBsmt'] = pd.Series(len(df_train['TotalBsmtSF']), index=df_train.index)

df_train['HasBsmt'] = 0

df_train.loc[df_train['TotalBsmtSF']>0,'HasBsmt'] = 1

#transform data

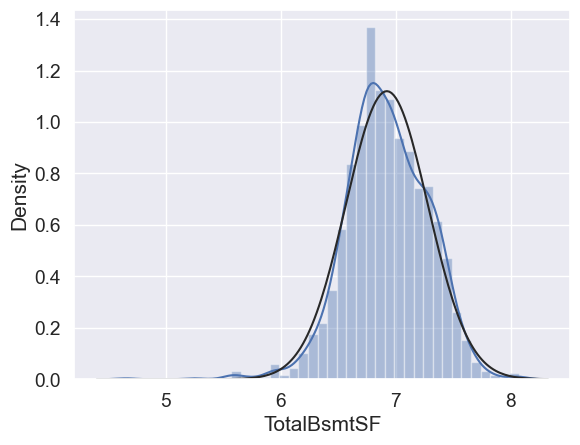

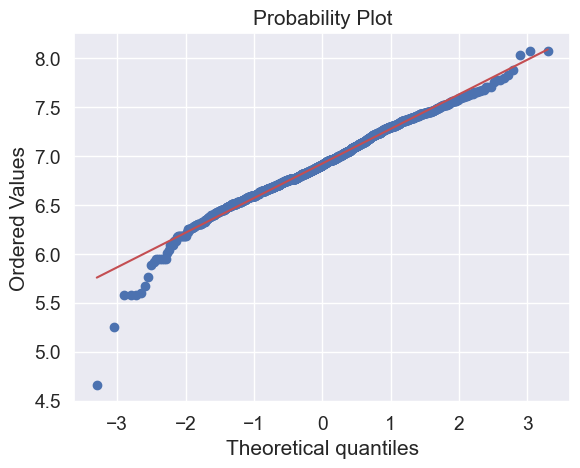

df_train.loc[df_train['HasBsmt']==1,'TotalBsmtSF'] = np.log(df_train['TotalBsmtSF'])

#histogram and normal probability plot

sns.distplot(df_train[df_train['TotalBsmtSF']>0]['TotalBsmtSF'], fit=norm);

fig = plt.figure()

res = stats.probplot(df_train[df_train['TotalBsmtSF']>0]['TotalBsmtSF'], plot=plt)

Homoscedasticity#

The best approach to test homoscedasticity for two metric variables is graphically. Departures from an equal dispersion are shown by such shapes as cones (small dispersion at one side of the graph, large dispersion at the opposite side) or diamonds (a large number of points at the center of the distribution).

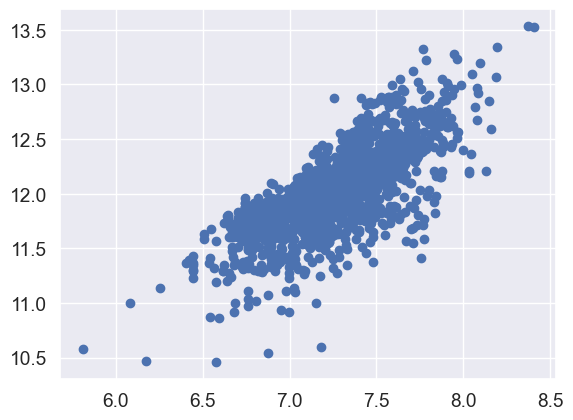

Starting by ‘SalePrice’ and ‘GrLivArea’…

#scatter plot

plt.scatter(df_train['GrLivArea'], df_train['SalePrice']);

Older versions of this scatter plot (previous to log transformations), had a conic shape (go back and check ‘Scatter plots between ‘SalePrice’ and correlated variables (move like Jagger style)’). As you can see, the current scatter plot doesn’t have a conic shape anymore. That’s the power of normality! Just by ensuring normality in some variables, we solved the homoscedasticity problem.

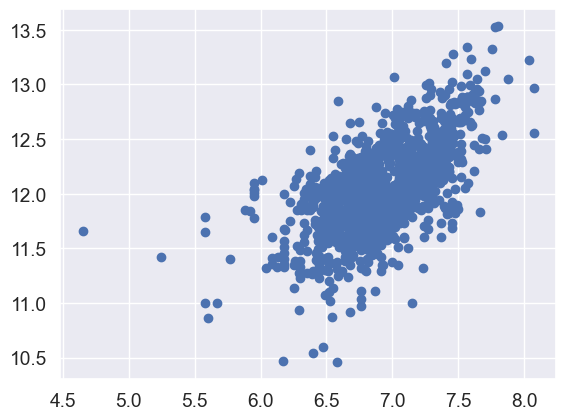

Now let’s check ‘SalePrice’ with ‘TotalBsmtSF’.

#scatter plot

plt.scatter(df_train[df_train['TotalBsmtSF']>0]['TotalBsmtSF'], df_train[df_train['TotalBsmtSF']>0]['SalePrice']);

We can say that, in general, ‘SalePrice’ exhibit equal levels of variance across the range of ‘TotalBsmtSF’. Cool!

Dummy variables#

Easy mode.

#convert categorical variable into dummy

df_train = pd.get_dummies(df_train)

Conclusion#

👉 We applied strategies from Hair et al. (2013), including:

Analyzing ‘SalePrice’ alone and with correlated variables

Handling missing data and outliers

Testing statistical assumptions

Transforming categorical variables to dummies

👉 Next steps:

Predict ‘SalePrice’ behavior

Consider different approaches:

Regularized linear regression

Ensemble methods

Other techniques

The choice of method is up to you to explore and determine